From scandal to success: Jan Van Beers

A new artistic genre?

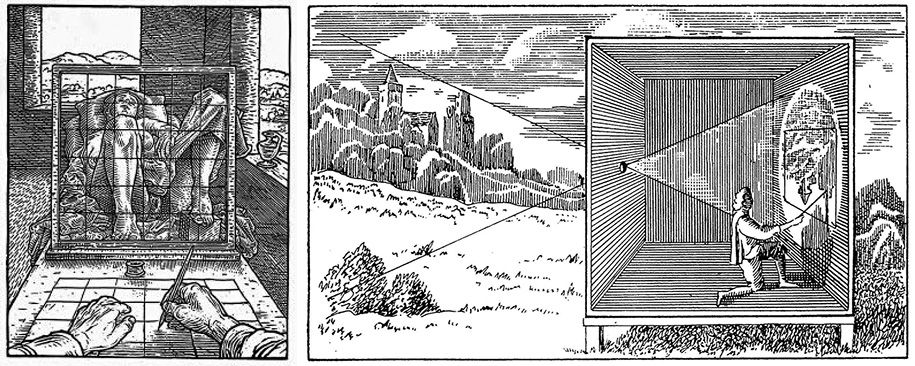

The 19th century was a period of intense mechanical innovation, not least the invention of photography. Artists had turned to technical aids for centuries to help them create their paintings. The ‘drawing machines’ of Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), for instance, and the camera obscura. Even using those tools, however, you still had to do the drawing yourself. Not so with a camera, which meant it was over and out for art. Or was it?

Machine à dessiner d’Albrecht Dürer et l’utilisation de la camera obscura comme dispositif

This was the essence of the debate that raged in the 19th century. To one person, a photograph lacks the soul inherent in true art. While to another, photography had to free itself from commerce and claim its status as an art form in its own right. Over the years, artists had gradually acquired a new status as creative geniuses. Were they now to be returned to the level of ‘mere’ craftsmen?

There was considerably more enthusiasm for photography beyond the world of art. Governments commissioned photographs of monuments, the military of battlefields, the police of prisoners, factories of their merchandise and the wealthy of themselves. Everything found its way into a photograph: pin-sharp and hyperrealistic. Yet all that realism was precisely what bothered some critics, who were already thoroughly irritated by the penchant in painting for works showing peasants and paupers.

Peintures d'histoire - En Belgique, Jan Van Beers se fait remarquer avec ses peintures d'histoire. Paris est moins enthousiaste. L'empereur Charles Quint enfant, KMSKA.

Urge to conquer

The flamboyant Jan Van Beers, who occasionally dressed up as Anthony van Dyck, left for Paris in 1878, all set to conquer what was then the epicentre of modern art. Sadly for him, things didn’t turn out that way: the fame and fortune he craved failed to fall into his lap. As an art student back in Antwerp, he’d been the golden boy – the future of painting. But his history paintings weren’t received anywhere near as well in Paris. It didn’t help that in the course of his ambitious pursuit of fame, he tried his hand at pretty much every existing genre, even preferring to mix several styles in a single work. Each of his paintings looks like it was done by a different artist, one critic mocked.

Van Beers learned his lesson and abandoned his earlier approach: from now on he would specialize in small and even miniature portraits. These were not just realistic, but hyperrealistic, finished with immense refinement down to the smallest detail. Numerous women in particular feature in his work, draped over sofas, elegantly dressed, daydreaming or clutching a book. This time the formula proved an instant success.

Van Beers se réinvente avec des portraits comme La femme en blanc (KMKSA) et cette jeune femme provenant d'une collection privée.

Van Beers se réinvente avec des portraits comme La femme en blanc (KMKSA) et cette jeune femme provenant d'une collection privée.

Scandal

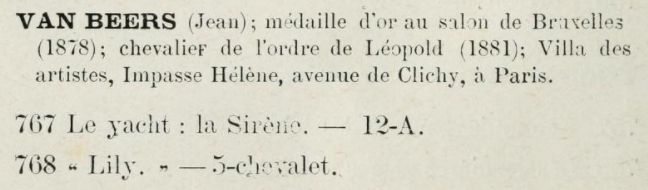

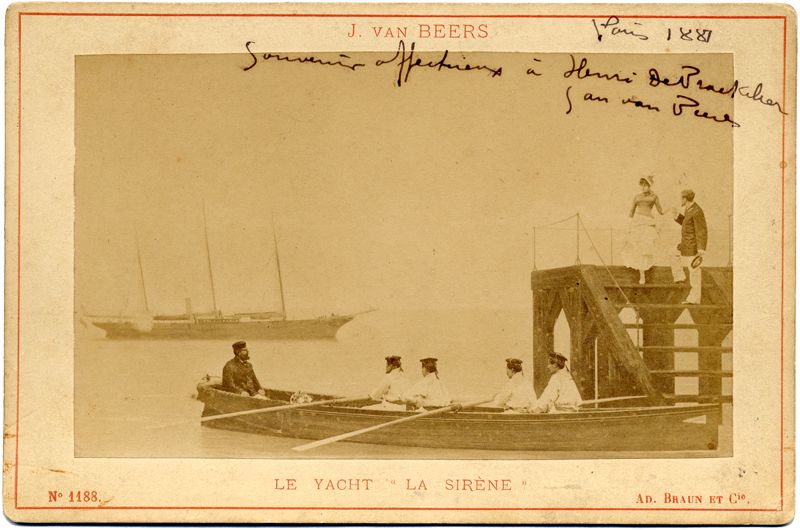

By August 1881, Van Beers had spent a good two years painting the Beau monde and so it was with confidence that he submitted two paintings to the annual Salon in Brussels: a little portrait entitled Lily and the somewhat more ambitious The Yacht ‘La Sirène’ in which an officer helps a woman board a rowing boat. Both works were done in his new style.

Salon de Bruxelles - Le catalogue du Salon de Bruxelles et la participation de Van Beers

It was at this point that all hell broke loose. Three critics declared that they could make out traces of a photograph beneath the paint of both works. Scandalous! How could a painter of great history works lower himself to mere overpainting, as if he were a simple craftsman? How could such a promising painter deceive his audience in this way? Why hadn’t he even bothered to conceal his deception? And why use photography at all? What a terrible example for new painters!

Van Beers fights back

The proud artist issued his critics with a challenge: he would allow them to remove the paint layer and if their accusations were proved correct, he would donate a sum of money. None of them responded to his proposal, but an unknown person did scratch away the head of the woman in La Sirène on 3 September, no doubt egged on by the fierce polemic that had been triggered not only in the newspapers but in many art magazines too. Supporters and opponents of the use of photography in painting began to make their voices heard all over Europe.

As for Van Beers, he wasted no time in assembling a jury to settle the matter once and for all. Eight men, including Charles Verlat, who taught at the Antwerp Academy, and two professors of chemistry and photography, set out their conclusions in a comprehensive report. In their view:

- Where the paint layer had been removed, the jurors detected an underdrawing in ink.

- The wealth of detail in La Sirène was too great for it simply to be an overpainted photograph.

- The format and proportions of the painting differed from those of photographs.

In summary: Jan Van Beers was vindicated.

Yet Lucien Solvay of La Gazette, one of the three original critics, was not convinced. There was still no proof that Van Beers had not used a photograph for reference and he might also have made a tracing of one.

This was the last straw for Van Beers, who sued Solvay for defamation. The court ruled, however, that anyone who exhibits their work in public automatically invites criticism. As far as the judge was concerned, Lucien Solvay had been perfectly entitled to question Van Beers’ methods. What’s more, rather than harming his reputation, L’affaire Van Beers actually catapulted the artist from marginal status to that of a star.

La Sirène - Carte postale de La yacht - La Sirène, Collection de la ville d’Anvers, Maison des Lettres

After the trial

Jan Van Beers’ popularity peaked after the trial. Having now achieved the wealth and fame he had dreamed of, he moved into an enormous house in Paris in 1892, where he decorated each room differently, filling it with exuberant and risqué details.

He kept hold of Lily and La Sirène and continued to exhibit them. After 1887, however, the two works fell off the radar, leaving just a postcard of La Sirène as evidence. It is not possible today to determine whether there was a photograph beneath the paint.

But what we do know for certain is that Van Beers used photographs as an aid for some of his work – his portrait of the musician Peter Benoit, for instance, of which the reference photo still exists.

Le compositeur Peter Benoît, Jan van Beers, KMSKA, et son pendant photographique.

The journey towards art photography

And what about photography? L’affaire Van Beers brought the taboo surrounding photography to the fore. Many painters at the time used photographs as a tool, but this was accepted in most artistic circles, provided no one drew attention to it. The benefits were obvious, after all: no more need to pose for hours on end, a visual aide-mémoire always to hand and also a quick way to reproduce works of art. Photographs were still frequently burned after use, however, to preserve the aura of the brilliant artist.

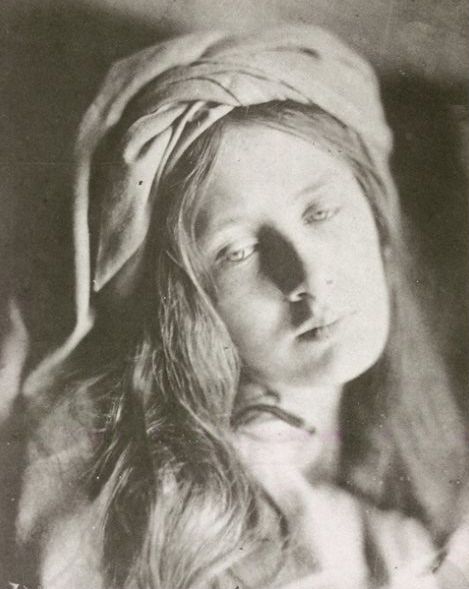

Photographers, meanwhile, still tried to align themselves with painting, using all sorts of experiments in an attempt to manipulate the end result and achieve a painterly effect. To be artists in their own right, rather than merely an extension of their apparatus.

La pionnière Julia Margaret - La pionnière Julia Margaret Cameron parvient à donner un élan artistique à la photographie.

At the same time, demand for realistic paintings – especially hyperrealistic ones – was in decline. Photography could simply do it better. Artists took the path of colour, imagination and expression instead. Until the 20th century, at least when different forms of realism staged a comeback with the likes of Andy Warhol or the Hyperrealism of the 1960s and 70s. Throughout all this, the essential question has been which is more important: the result or the path leading to it?